If you watched a lot of

network television in the 80’s and 90’s, then you’re probably familiar with a

concept called the “Very Special Episode”, where a normally lighthearted show (usually

family sitcoms) would take an abruptly serious tone shift in order to teach the

audience a lesson about serious topics like drug and alcohol abuse, stranger

danger, racism and even sexual assault. They’re not nearly as common as they once

were, mostly because they’ve been the subject of ridicule for trying to offer

concise, clean-cut solutions to complicated subject matter with no easy answer.

It’s precisely because of this that Luce, a psychodrama that tackles a

myriad of complex topics but offers no simple solutions, feels so refreshing.

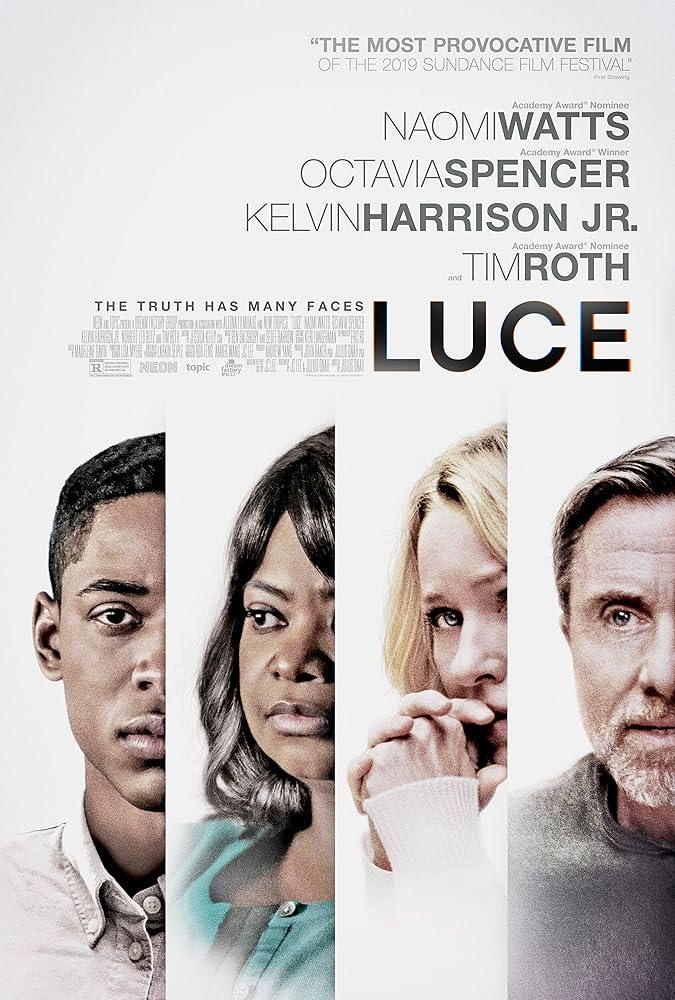

Our story follows Luce (Kelvin

Harrison Jr.), a black teenager who was raised as a child soldier in a war-torn

African nation, but is given a new lease on life after he’s adopted by a white

couple (Naomi Watts and Tim Roth) and brought to America. Since then, he’s completely

turned his life around. He’s a star athlete, a model student, and is beloved by

peers and teachers alike. But one day, his history teacher Harriet (Octavia

Spencer) makes a horrifying discovery. He writes a paper advocating for

violence against political opponents, and to make matters worse, a bag full of

illegal fireworks are found in his locker. Luce’s parents are understandably in

denial and do everything they can to defend him, which becomes harder as more evidence

comes pouring in and the already antagonistic relationship between Luce and

Harriet becomes more hostile.

To say this film is topical

would be underselling it. In a time where America suffers a mass shooting

nearly every day, often telegraphed by the shooter writing a manifesto

declaring its radical worldview, and the tightening scrutiny of black people by

the police, it’s hard not to see why a film like this would need to be made.

Director Julian Onah, who rebounds here after his career got off to a rocky

start with The Cloverfield Paradox, provides an uncomfortably real

situation to life where there are no easy answers, no easy solutions, and no

one is exactly who they say they are.

In the paper that sets the

plot in motion, Luce writes in the voice of Frantz Fanon, a pan-African philosopher

who famously argued that violence was a necessary component in the fight

against tyranny. This understandably sets off a few alarm bells, and combined

with his troubled upbringing, makes him look like a radical in the making. But

aside from Harriet, the rest of the faculty is less eager to put the screws on

him since he’s become a poster boy for the school’s successes, and don’t want

to tarnish that reputation. While Luce repeatedly insists that he’s innocent, there

was always tension between him and Harriet, who has a take-no-prisoners approach

to teaching her students about the propensity of tokenism by singling certain

students out for not living up to her expectations. This has led to a female

student being outed after she was sexually assaulted at a party, and a

promising young athlete getting kicked off the track team and having his chance

at a college scholarship jeopardized for smoking weed. (Not coincidentally,

both students are minorities.) Likewise, Luce’s parent’s end up in a similar

nature vs. nurture conflict since the onus is on them to raise him right.

Understandably defensive of their son at first, as the evidence against him

piles up, they start to question if there was anything they even could

do.

But while the adults are busy

pointing fingers at each other, Luce is under the pressure of both this scandal

and everyone’s colossal expectations of him. But rather than cracking, he feels

somewhat content into slipping into the roles forced onto him. Performances are

excellent all around, and while that’s expected when you have the likes of

Watts, Roth and Spencer in your cast, it’s Kelvin Harrison Jr. who ends up

leaving the most lasting impression. Able to switch between coding on a dime,

he slips into the roles of son, student, friend and adversary with nary a

hitch, all while maintaining a sinister congeniality that never quite gives

away what’s going on in this character’s head. At once frustrated by the

various boxes his parents, teachers, and society try to force him in, hungry to

right perceived injustices, and maybe a little too eager to exact revenge on

those who put him in this conundrum, Luce remains an enigma, a question mark trying

to straighten himself into an exclamation point.

At the end of the day, Luce

feels more like a film that’s meant to be discussed than enjoyed. That

persistent vagueness may be a sticking point for some looking for clear cut

answers, but if there is any lesson to take away from this, it’s that there

aren’t always clear-cut answers, defined good guys or bad guys for us to extract

catharsis from. This ambiguity will probably be the defining factor that’ll

make this movie relieving or maddening for the audience, but it’s a necessary

one nevertheless.

8/10

No comments:

Post a Comment