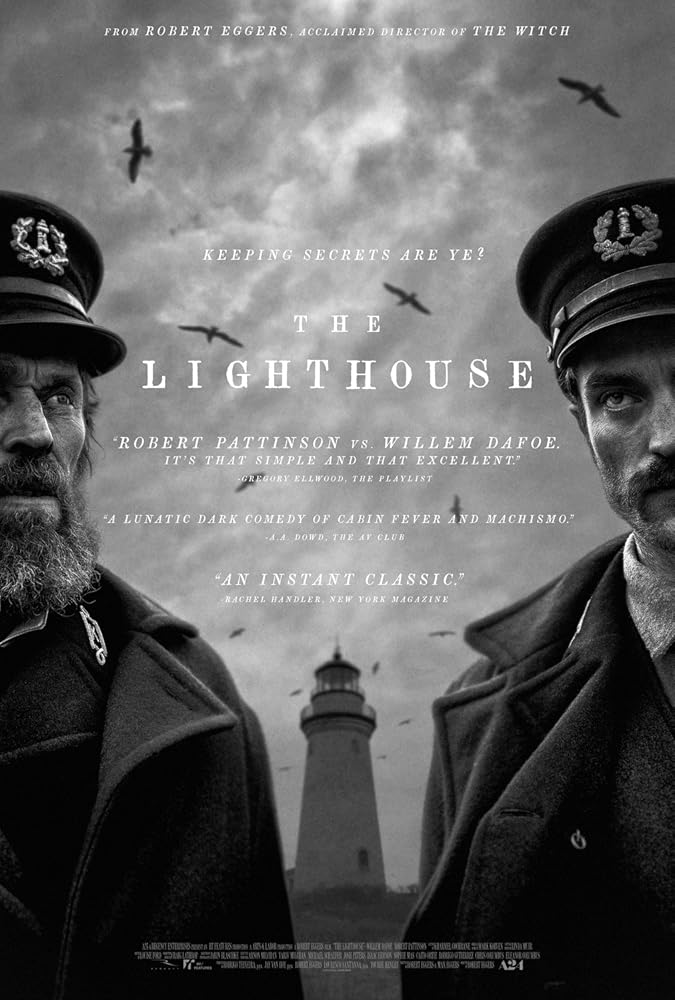

Robert Eggers arrived onto the

scene in 2016 with The Witch, a tense, atmospheric period piece where a

puritanical family on the edges of civilization tears itself apart after being

cursed by a witch, but half the time you’re left wondering if their paranoia is

their own doing or that of outside forces. The Lighthouse operates on

the same principle, only the supernatural forces at play are more vague, and

considering our two characters are already so far gone and on such different

ends of the spectrum that they wouldn’t need outside aid to go mad.

Our story is set in the 1890’s

and follows two lighthouse keepers: Thomas Wake (Willem Dafoe), a superstitious veteran

wicky who’s rough as a bed of barnacles and salty as the sea herself, and

Ephraim Winslow (Robert Pattinson), a reserved former lumberjack looking to

turn a new leaf. The two are left on a rock together for a month of back

breaking labor, manning a lighthouse far off the coast of Maine. Ephraim does most

of the day labor, feeding the furnace, filling up the oil pit and cleaning the cabin,

while Thomas barks demeaning orders and hogs the nightly duty of keeping the

lantern lit. It doesn’t take long for them to get sick of each other’s company,

but when the boat that’s supposed to take them home doesn’t arrive, the

isolation takes its toll and threatens their already fragile sanity.

By design, The Lighthouse

feels like an old forgotten horror film from the 1940’s that never saw the

light of day until it was rediscovered in a basement somewhere. Shot in

stunning black and white with antique equipment and framed by a claustrophobic

1.19:1 aspect ratio, with dialogue that wouldn’t be out of place in the works

of Melville, Hemmingway or Lovecraft, while also letting the actor’s faces do

most of the talking, there’s a certain antiquity to this film’s presentation.

And for all the sea shanty vernacular that spills from these character’s mouths

like fish from a net, it also knows when to let the silence do all the work. It’s

a good ten minutes before either of them speaks (we hear Willem Dafoe’s fart

before we hear his voice), and it’s at least 45 minutes before either learn

each other’s names.

That tight, square aspect

ratio makes the audience feel like it’s watching their descent into madness

through a peephole or the cracks of a fence, squeezing us in to the already

close quarters with them. The lighthouse is just as much of a character as

Thomas or Ephraim; a large, looming beacon that creeks and moans whenever

someone so much as pumps the water spout, blurts out its whale song of a

foghorn throughout the night, and whose piercing bright light holds some

hypnotic quality that affects everything in its radiant glow. Eggers’s past career

as a set designer is evident here. Although the cabin and the lighthouse were

both built from the ground up specifically for this movie, it looks like

something that has stood vigil on the craggy shores for 150 years.

It’s a two-man show with Dafoe

and Pattinson giving two of the most unforgettable performances of the year,

and possibly their entire careers. They drag each other into the cold, dark,

briny depths of madness, with each experiencing their own unique flavor of

insanity. Dafoe’s character is an archetypal salty sea captain that’s so over

the top that he might as well be a cartoon character. He’s a harsh, tyrannical

slave driver when sober, and a jaggedly elegant wordsmith when drunk (which is

basically every night). Pattinson, meanwhile, is quietly seething with resentment,

slowly broken by his flatulent overseer’s abuse and the grueling labor he puts

him through. Aside from shoveling coal and oil day in day out, mending the

perpetually leaky ceiling and floorboards and getting piss blown back in his

face when he empties the chamber pot, he’s haunted by visions of a mermaid that

he violently relieves himself to, and taunted by a stubborn seagull that mocks

him at every turn.

But the thing that threw me

off guard, and what made this movie so palatable, is how surprisingly funny it

is. Where The Witch was a burning crucible of religious paranoia, The

Lighthouse is no less intense, but is just as much a tale of two terrible

roommates as it is Lovecraftian horror, and always breaks up the tension in the

most unexpected moments. Those interactions between Ephraim and the seagull,

while eventually reaching a grizzly end and later ramifications that recall Poe’s

raven or Coleridge’s albatross, is also comparable to Bill Murray’s battle with

the gopher in Caddyshack. When they run out of food and are forced to

sustain themselves on booze, they switch between fisticuffs, singing and

dancing, hurling insults, and tender moments that nearly turn homoerotic

subtext into text. By this time, all sense of time, reason and sanity has

completely slipped away, until they’re left playing the world’s most demented

game of house. Like Eggers said in a Hollywood Reporter interview, “Nothing good

can come when two men are trapped alone in a giant phallus.”

Bottom line, The Lighthouse

is an eerie, funny, fascinating, mesmerizing little gem that works equally well

as an artistic mood piece and a pitch-black comedy. It’s a strikingly unique

psychological exorcism of the mania of isolation, loneliness and repression

that recalls the literary and cinematic classics but fashions them into a weather-beaten

patchwork that could withstand the most violent of hurricanes. Robert Eggers’s

next project will be about Vikings, and rumor has it that he’s in line to work

on a remake of Nosferatu. After seeing this, I couldn’t think of a

better person for the job.

10/10

No comments:

Post a Comment